958

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Indigenous knowledge is, broadly speaking, the

knowledge used by local people to make a living in a particular environment.

This study aimed to study the traditional practice of cereal legume cropping

system and document the indigenous traditional community knowledge of soil

fertility improvement by farmers in Tigray region of Ethiopia. In addition, it

attempted to assess the existing knowledge of farmers about the role of

microbes in improving soil fertility during legume-cereal cropping.

A total of 71 farmer-informants were selected using

simple random sampling technique from the study area. A pre-tested and adjusted

semi-structured interview questionnaire was designed and administered to

explore farmers’ soil classification techniques, farmers’ indigenous and

inherent techniques of soil fertility assessment, cropping systems and their

knowhow about microbes associated with legume nodules and their effects in the

improvement of soil fertility and growth of crops. Descriptive frequency

statistics (Central tendency, dispersion and percentiles) was used to evaluate

all the variables using SPSS (2011) software ver.20.

The three most common farming practices carried out

by farmers in all study provinces (woredas)

are; strip cropping (82% of respondents), crop rotation (79% of respondents),

and mono-culture cropping (54% of respondents), respectively. The most common

types of crops they combine during crop rotation are sorghum, teff, barley,

maize and chick pea. Twenty eight percent of the respondents follow this

combination of cereal and legume crops in their crop rotation farming system.

This study also found out that most farmers living in the study area are aware

of the role of legumes in soil improvement but they were not able to reason out

how legume root nodules help the enhancement of soil fertility.

INTRODUCTION

Indigenous knowledge (IK) is, broadly

speaking, the knowledge used by local people to make a living in a particular

environment [1]. It can be defined as “A body of knowledge built up by a group

of people through generations of living in close contact with nature” [2]. The

term “Indigenous knowledge” sometimes refers to the knowledge possessed by the

original inhabitants of an area, while the term “local knowledge” is a broader

term which refers to the knowledge of any people who have lived in an area for

long period of time. As stated by Langill [3], such knowledge evolves in the

local environment so that it is specifically adapted to the requirements of

local people and conditions. It is also creative and experimental, constantly

incorporating outside influences and inside innovations to meet new conditions.

Langill [3] further advised that considering indigenous knowledge as “old

fashioned”, “backwards”, “static” or “unchanging” is a big mistake. Thus,

studying traditional indigenous knowledge of a community and documenting it is

not a simple task of gathering former knowledge but it is an act of searching

tremendous knowledge originated and developed for many generations in a

particular population through social experimentation and creation.

Farmers in different parts of the world

practiced different traditional cropping systems. Legume-cereal cropping is one

of the most frequently employed farming systems. Legumes are potential sources

of plant nutrients that complement/supplement inorganic fertilizers for cereal

crops

Crop rotation is a practice of

rotating/changing the type of crops grown in the field each season or each year

(or changing from crops to fallow). It is a key principle of conservation

agriculture because it improves the soil structure and fertility, and because

it helps control weeds, pests and diseases [5]. Farmers in ancient cultures as

diverse as those of China, Greece, and Rome shared a common understanding about

crop rotations. They learned from experience that growing the same crop year

after year on the same piece of land resulted in low yields and that they could

dramatically increase productivity on the land by cultivating a sequence of

crops over several seasons. They came to understand how crop rotations,

combined with such practices as cover crops and green manures, enhanced soil

organic matter, fertility and tilth [6].

Intercropping is also an ancient practice,

placed on the fringes of a ‘modern agriculture’ dominated by large areas of

monocultured, resource-consuming and high-yielding crops. Intercropping is

considered as a means to address some of the major problems associated with

modern farming, including moderate yield, pest and pathogen accumulation, soil

degradation and environmental deterioration, thereby helping to deliver

sustainable and productive agriculture [6]. It involves two or more crop

species or genotypes growing together and coexisting for a time. This latter

criterion distinguishes intercropping from mixed monocropping and rotation

cropping. Intercropping is common, particularly in countries with high amounts

of subsistence agriculture and low amounts of agricultural mechanization [5].

Developing countries such as Ethiopia, Niger,

Mali China, India, and Indonesia have shown considerable interest in

intercropping to enhance productivity [7]. In particular, cereal/legume

intercropping is commonly employed in China and sub-Saharan Africa and has

shown over-yielding and nutrient acquisition advantages under adverse

conditions. Furthermore, intercropping also provides an important pathway to

reduce soil erosion, fix atmospheric N2, lower the risk of crop

failure or disease and increase land use efficiency [7].

Intercropping is often undertaken by farmers

practicing low-input (high labor), low-yield farming on small parcels of land.

Under these circumstances, intercropping can support increased aggregate yields

per unit input, insure against crop failure and market fluctuations, meet food

preference and/or cultural demands, protect and improve soil quality, and

increase income. Intercrops can be divided into mixed intercropping

(simultaneously growing two or more crops with no, or a limited, distinct

arrangement), relay intercropping (planting a second crop before the first crop

is mature), and strip intercropping (growing two or more crops simultaneously

in strips, allowing crop interactions and independent cultivation) [5].

Various types of intercropping were known and

presumably employed in ancient Greece about 300 B.C. Theophrastus, among the

greatest early Greek philosophers and natural scientists, notes that wheat,

barley, millets and certain pulses could be planted at various times during the

growing season often integrated with vines and olives, indicating knowledge

of the use of intercropping [8].

Traditional agriculture, as practiced through the centuries all around the

world, has always included different forms of intercropping. In fact, many

crops have been grown in association with one another for hundred years and

crop mixtures probably represent some of the first farming systems practiced

[9]. Now a day, intercropping is commonly used in many temperate, tropical and

subtropical parts of the world particularly by small-scale traditional farmers

[10]. Traditional multiple cropping systems are estimated to still provide as

much as 16-22% of the world’s food supply [11].

In Ethiopia, plow agriculture in its current

form as a dominant tool appears in rock painting dating as far back as 500 AD.

This annual crops (grain, legume and oil seed) based plow agriculture was

centered in the central and northern highlands of Ethiopia. Tigray is located

in the Northern major highlands of Ethiopia. Even though it is difficult to

find complete and exact information when and where crop rotation, intercropping

and other traditional cropping systems were started in Ethiopia, it is

understood that the practice of cropping began many centuries ago. By fixing

atmospheric N2, legumes offer the most effective way of increasing

the productivity of poor soils either in monoculture, intercropping, crop

rotations or mixed cropping systems. These cropping systems are commonly used

in many temperate, tropical and subtropical parts of the world particularly by

small-scale traditional farmers. This study aimed to study the traditional

practice of cereal legume cropping system and document the indigenous

traditional community knowledge of farmers in Tigray region of Ethiopia. In

addition, it attempted to assess the existing knowledge of farmers about the

role of microbes in traditional cropping systems, especially in legume-cereal

cropping, in a systematic way.

MATERIALS AND

METHODS

Description of study

area

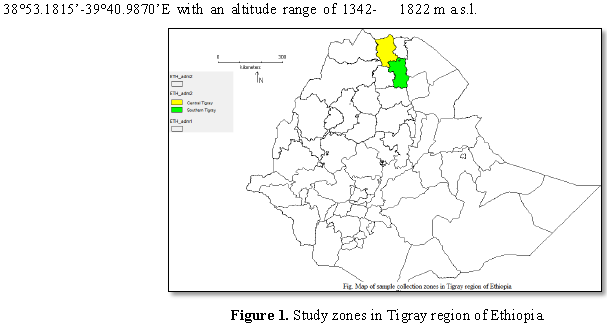

Data collection was undertaken in 8

administrative units (kebeles) of 3 woredas

in Tigray region of Ethiopia, which were considered to be representative of the

practice of cereal-legume cropping system in the highland areas of Ethiopia. A

semi-structured interview based survey was used to collect the data [12,13]. In

each kebeles, the research team randomly selected a representative group of

farmers with different ages and social classes. The team used interview guides

from the study woreda agricultural

office during individual and group discussions so that the team members easily

understand farmers’ perceptions of soil fertility, techniques of soil

classification, and their cropping systems. They also attempted to assess

farmers’ knowledge/knowhow of microbes associated with legumes and their

effects in soil fertility improvement [12,13].

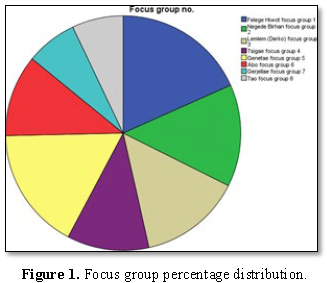

Seventy one farmer-informants were selected

using simple random sampling technique from the study area. Semi-structured

interview questionnaire was designed and administered to explore farmers’ soil

classification techniques, farmers’ indigenous and inherent techniques of soil

fertility assessment, cropping systems and their knowhow about microbes

associated with legume nodules and their effects in the improvement of soil

fertility and growth of crops. The semi-structured interview questionnaire was

pre-tested and adjusted before its full administration [12]. The questionnaire

was administered by researchers working in Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute,

microbial biodiversity directorate; bacteria and fungus case team and

agricultural experts working at the study areas. Focus group discussion was

made with members composed of representatives of each kebele who were community

elders and young farmers who have been engaged in farming. 8-12 informants in

each focus group were included for the study [12].

Data analysis

Descriptive frequency statistics (Central

tendency, dispersion and percentiles) was used to evaluate all the variables

using SPSS (2011) software ver.20. ANOVA was done to compare the mean values of

the variables. P-value less than 0.5 were taken as significance.

RESULTS AND

DISCUSSION

Characteristics of respondents/informants

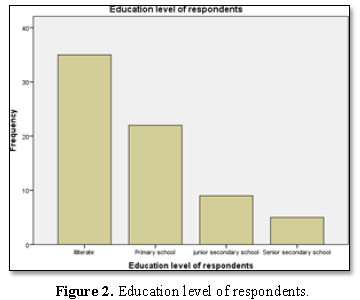

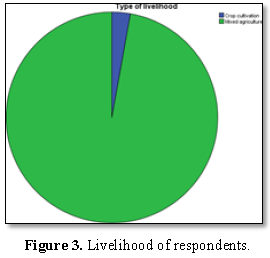

Farmer informants who were included in the

study were from different age group, education level and livelihood background.

The mean age of the informants was 48 and their mean family size was 6. Their

education level was also different. 49% of the respondents were illiterates but

51% of them completed either primary and/or secondary school (Figure 2). Ninety three percent of the

total informants lead their life by engaging in mixed agriculture and the rest

3% rely only on crop cultivation (Figure

3).

Farmers’ techniques of soil classification

This study indicates that farmers living in

the two zones of Tigray have various techniques of traditional practices

adopted for classification of soil. All of the respondents answered that they

basically use soil color, soil texture and gravel content of the soil as

criteria to classify soil. Different types of soil color are used by farmers in

all kebeles of the study areas. The

major soil color types used by farmers are black, brown, red and gray. In

addition, three major types of soil texture; rough, smooth and muddy are most

often used by all farmers in the study area. They adopt different methods to

assess the soil texture. Observation by eye, hand touch and ploughing are the

most important methods frequently adopted by farmers to differentiate the soil

roughness or smoothness.

Farmers’ techniques

of soil fertility assessment

Farmers in the study area do have tremendous

indigenous and inherent techniques of soil fertility assessment. Even though

they traditionally adopt various techniques of soil assessment, they most

frequently use soil color and texture change, productivity decline, appearance

of sand in the field, poor seedling germination immediately after sawing,

yellowing and other coloration of crop leaves during crop growth,

dicotyledonous weeds occurrence and soil fauna (earth worm casting activity),

soil workability, slope and the soil’s depth criteria. Sixty eight percent of

the respondents explained that they use these criteria in combination in their

day to day activity of farming. Fourteen percent of the respondents use this

criterion in combination except soil fauna (Earth worm casting activity),

appearance of sand in the field and poor seedling germination immediately after

sawing to assess the soil fertility.

Forty two percent of the respondents

explained that they consider the soil is fertile if the soil has black color,

smooth texture and has high water holding capacity. But, fourteen percent of

the respondents said that they take the soil fertile if it is also red in color

but smooth in texture. In general terms, farmers give soil rank as fertile if it

has black color, red color, gray color and brown color, respectively.

Farmer respondents explained that they use

dicotyledonous weeds occurrence as a means to tell whether the soil is either

fertile or infertile. It is found that 15 types of dicotyledonous weeds are

used by farmers as indicators of fertile soil. They also mentioned another 9

types of dicotyledonous weeds that are used by them as indicators of infertile

soil. The most commonly used fertile soil indicator weed is gemale (39.44% of

respondents) which is followed by weed mestenagir (36.62% of respondents) and

hitsihitsi (28.13% of respondents). On the other hand, akenichira (100% of

respondents) is the most frequently employed infertile soil indicator weed

followed by kinche (53.5% of respondents) and eshoh mergem (28.2% of

respondents).

Farmers’ methods of

cropping systems and their knowledge about the role of microbes associated with

legume root nodule

This study showed that farmers in Tigray

district practice different types of cropping systems. They perform one or the

other cropping system at different time; Mono-cropping, crop rotation,

intercropping, sequential cropping, and strip cropping. The three most common

farming practices carried out by farmers in all study woredas are; strip cropping (82% of respondents), crop rotation

(79% of respondents) and mono-culture cropping (54% of respondents),

respectively.

The main reason farmers responded why they

rotate crops from seasons to seasons is to increase yield, improve soil

fertility and control weeds, pests and diseases. Around 82% of the respondents

practiced crop rotation in every other year. The rest respondents practiced

crop rotation in less than year time. The most common types of crops they

combine during crop rotation are sorghum, teff, barley, maize and chick pea.

Twenty eight percent of the respondents follow this combination of cereal and

legume crops in their crop rotation farming system. A sorghum, teff and sesame

seed is the next common combination of crops followed by farmers during crop

rotation time.

Farmers consider different factors in

selecting the right crops to combine them for crop rotation system. The major

criteria they follow are ability of the combined crops in complementing one

another (44%), ability of the crop in improving the soil fertility (42%) and

ability of the crops in covering the soil (39%), respectively. Only 17% of the

respondents included in the study accounted the type of roots the crops have is

used in selecting the right crops to combine in crop rotation practices. Forty

four percent of farmers living in the study district also have frequent

practice of using fallow land for crop rotation rather than combining crops.

They take five years on average of duration of fallow land period between two

consecutive crop rotations.

All of the farmer respondents are aware of

the difference between the root types of cereal and legume crops. Eighty six

percent of the farmers do not have the knowhow about the association among the

roots, root nodules and N2 fixation carried out by microbes

associated with legume roots. But, in the contrary to this fact 89% of the

respondents are found to have the knowledge about the importance or the role of

legume crops during crop rotation in the improvement/enhancement of soil fertility.

This indicates that most farmers living in the study area are aware of the role

of legumes in soil improvement but they do not have the scientific background

about the role of microbes associated with legume root nodules in the

enhancement of soil fertility [14,15].

CONCLUSION

The three most common farming practices

carried out by farmers in all study provinces (woredas) are; strip cropping (82% of respondents), crop rotation

(79% of respondents), and mono-culture cropping (54% of respondents), respectively.

The most common types of crops they combine during crop rotation are sorghum,

teff, barley, maize and chick pea. Forty five percent of farmer respondents

living in the study district also have the practice of using fallow land for

crop rotation rather than combining crops. They take five years on average of

duration of fallow land period between two consecutive crop rotations.

This study further more indicated that

farmers in the study area do have tremendous indigenous and inherent techniques

of soil fertility assessment. Even though most of them are aware of the role of

legumes in soil improvement, they do not have the scientific background about

the role of microbes associated with legume root nodules in the enhancement of

soil fertility as indicated in other study done by the same authors of this

study in North Shoa of Ethiopia.

1. Warren DM (1991) Using indigenous

knowledge for Agricultural development. World Bank Discussion Paper 127.

Washington D.C.

2. Johnson M (1992) Lore: Capturing traditional

environmental knowledge. IDRC: Ottawa, Canada.

3. Langill S (1999) Indigenous

knowledge: A resource kit for sustainable development researchers in dry land

Africa. People, land and water initiative. IDRC: Ottawa, Canada.

4. Massawe PI, Mtei KM, Munishi LK,

Ndakidemi PA (2016) Improving Soil fertility and crops yield through

maize-legumes (Common bean and Dolichos lablab) intercropping systems. J Agric

Sci 8.

5. Brooker RW, Bennett AE, Cong WF,

Daniell TJ, George TS, et al. (2015) Improving intercropping: A synthesis of

research in agronomy, plant physiology and ecology. New Phytol 206: 107-117.

6. Baldwin KR (2006) Organic

production-Crop rotations on organic farms. Centre for environmental farming

system. Available at: http://www.oacc.info/Docs/Cefs/Crop_Rotations.pdf

7. Wang ZG, Jin X, Bao XG, Li XF,

Zhao JH, et al. (2014) Intercropping enhances productivity and maintains the

most soil fertility properties relative to sole cropping. PLoS One 9: e113984.

8. Papanastasis VP, Arianoutsou M,

Lyrintzis G (2004) Management of biotic resources in ancient Greece. In:

Proceedings of 10th Mediterranean Ecosystems (MEDECOS) Conference,

Rhodes, Greece 25: 1-11.

9. Plucknett DL, Smith NJH (1986)

Historical perspectives on multiple cropping. In Multiple Cropping Systems,

Francis CA, Ed. New York, USA: MacMillan Publishing Company.

10. Altieri MA (1991) Traditional

farming in Latin America. Ecol 21: 93-96.

11. Altieri MA (1999) The ecological

role of biodiversity in agroecosystems. Agric Ecosyst Environ 74: 19-31.

12. Grenier L (1998) Working with

indigenous knowledge: A guide for researchers. International Development

Research Centre, Ottawa, ON, Canada K1G 3H9.

13. Pretty J, Guijt I, Thompson J, Scoones

I (1995) A trainer’s guide for participatory approaches. IIED. London.

14. Encyclopedia Britannica (2017)

Shewa Encyclopedia Britannica Inc. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Shewa

15. McCann JC (2017) Oxford Research

Encyclopedia of African History: The History of Agriculture in Ethiopia.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

-

SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Journal of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine (ISSN:2641-6948)

- Journal of Veterinary and Marine Sciences (ISSN: 2689-7830)

- Food and Nutrition-Current Research (ISSN:2638-1095)

- Journal of Genomic Medicine and Pharmacogenomics (ISSN:2474-4670)

- Advances in Nanomedicine and Nanotechnology Research (ISSN: 2688-5476)

- Journal of Astronomy and Space Research

- Journal of Microbiology and Microbial Infections (ISSN: 2689-7660)